Dark-Eyed Babies Of The World

Dear Doodlebug:

Each morning when my alarm rings, your tuxedo cat Zoey jumps up the foot of the bed and climbs on top of me, licking my face in anticipation of being fed. At eleven pounds, Zoey is the weight of my smallest kettlebell, and after scratching a little around her neck (which you know she loves), I have to push her off so I can breathe.

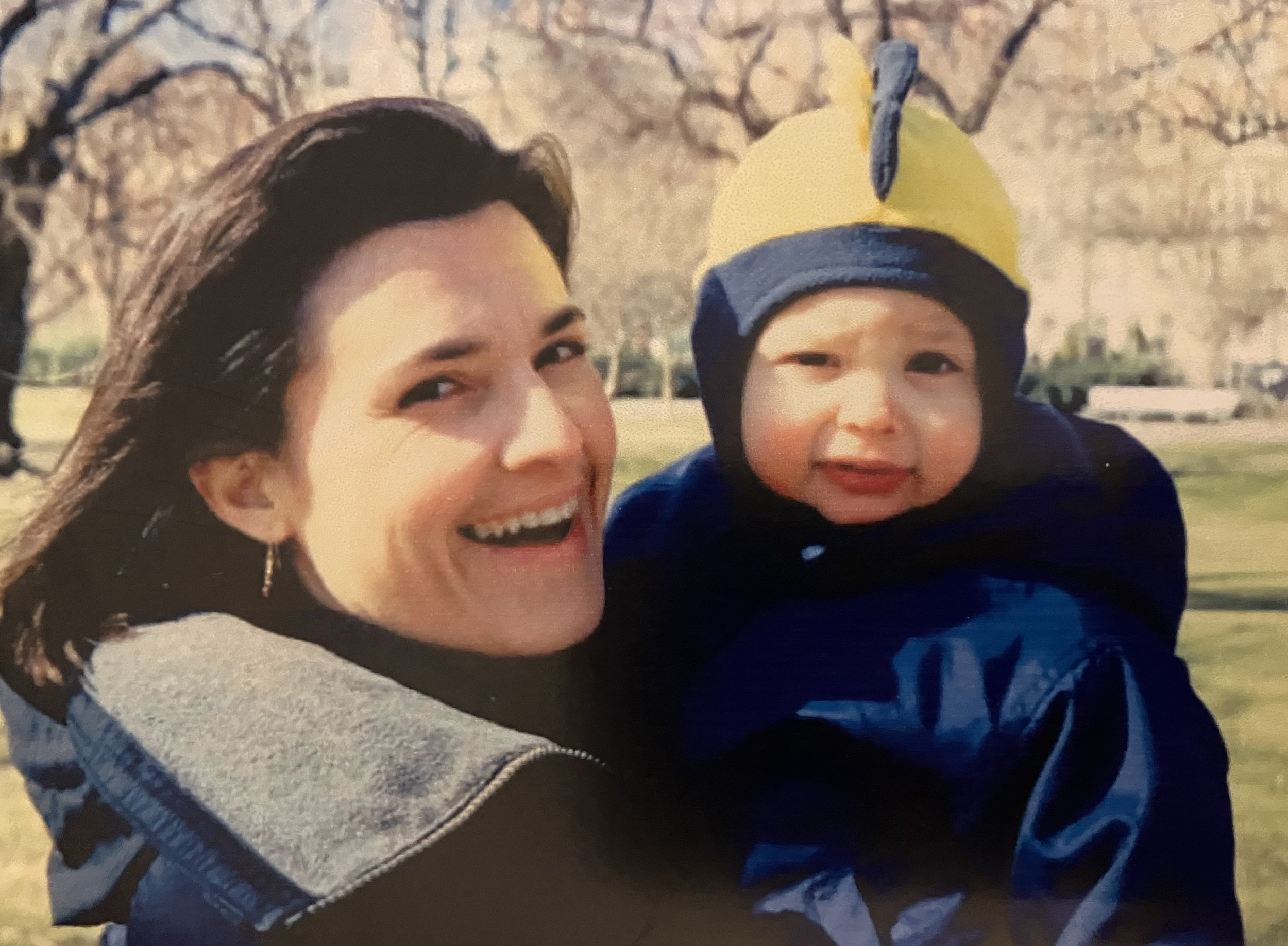

Eleven pounds is what you weighed when I brought you home from the hospital 58 days after your birth. For the first year of your life, you slept on top of me every night, an increasingly heavy but reassuring weight. I had begun to sleep that way at Boston Children’s Hospital after waking up with no baby in the room. The nurses would have spirited you off because of a dislodged feeding tube or low blood sugar, or because they wanted to feed you. They said it was so I could sleep, but I knew it was because you were the only newborn on the endocrine ward and irresistibly cute. Dark hair, big dark eyes like pools of velvet. A real charmer, as your Papa would say.

Rolling over to see an empty isolette filled me with terror. Were you seizing or choking on aspirated fluid; was your blood sugar plummeting? I would spring out of bed, calling, “Does anyone know where my baby is?” and wander the halls until I found you. But if you were sleeping on my chest—and nature wires mothers to wake up at the slightest sound—I would sense the crisis first. The nurses couldn’t take you away to play house without alerting me. I had ticked away too many abject hours outside the door of the procedure room, nicknamed the “boo-boo room,” where they reinserted a dislodged feeding tube or an intravenous line in veins as small as embroidery thread, to let that happen again. Whatever I imagined them doing to you was far worse than reality, though hearing you cry made my breasts leak milk and my insides quiver. You were inside me for almost ten months. After childbirth, my body still registered your pain.

It does, to this day.

One memory, more than any other, seems to presage our current state of estrangement born, like all estrangements, from angers and alliances that brewed before your birth.

In the wee hours of a late September morning, I walked with you in my arms to the pre-op room at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. The five prior weeks in the Children’s Hospital of Boston hadn’t ended with cure. You were now diagnosed with a rare form of hyperinsulinism (too much insulin, which depresses blood sugar), a disease then treatable at only three hospitals in the world: in Jerusalem, Paris, and Philadelphia. I have undertaken exhaustive therapy to heal the grueling ordeal at Boston Children’s Hospital, including the suspicion that I—recovering from a C-section—was intentionally making you sick. The doctors hadn’t seen ever your disorder; after a series of unsuccessful interventions, they suspected me. That blame was stoked by your father’s irrational insistence that I would hurt you, a fear born of his own anxiety and high-profile stories of depression-fueled infanticide. Twenty-four years later, I still have nightmares of crawling on pavement barefoot and in only my nightgown, trying to get home to you. When the insurance company finally gave us clearance, we were ambulanced to a Lear jet and delivered, Boston to Philadelphia, in forty-four minutes. You were this little lima bean on huge gurney, a red pulse oximeter on your big toe, all smiles.

Those forty-four minutes saved your life. The fallout of misdiagnosed hyperinsulinism is permanent brain damage. I saw it firsthand in Manal, one-year-old in the hospital crib beside yours. She could neither sit up, babble, nor hold a cookie. “I want for my daughter the same,” her mother said hopefully in an Arabic accent, after you were cured. I casually shared that communication with your doctor, who conveyed with a shake of his head that Manal’s brain damage was tragically permanent. Seeing that toddler who would never toddle, her abundant brown hair tied with pink ribbons and her big chocolate eyes wandering but not focused, I understood how nearly we had come to disaster.

The doors to the pre-op room opened at six-thirty in the morning. A Russian nurse reached for you, saying, “Vee prom-ees to take goot care of heem.” I sobbed brokenly as your body slid out of my arms. The surgical consent forms listed death as a possible risk, and I wondered if I would see you again. Then your father said, “Goodbye, Zachariah,” a term of endearment that would vanish when we split up (had he known it was a Christian name, he later said, wouldn’t have agreed to it, but I had chosen it because of its meaning to both Christians and Jews: “The one remembered by God”).

I kissed your forehead, as delicate as a damp eggshell, and said, “I love you, Zack.”

Then the nurse carried you away.

You faced ten hours in the OR, the surgeon said, and advised us to leave the hospital for a much-needed break. But I was exhausted and dirty. I had no clean clothes and no laundry detergent; for six weeks, I hand-soaped and rinsed our clothes in the sink and hung them over the radiator to dry. All my maternity attire was yards too big, and my clogs were run over on the sides from pacing. My short hair had grown out and was flat and unmanageable; my fingernails, bitten down to stubs. Your hospital bed in the endocrine ward was already assigned to another child, and I needed to pack up our stuff. But I fell onto your bed, unable to resist sleep.

An hour later, your father shook me awake.

“The nurse just called—they’re finished!”

Finished with what?

“The surgery!”

I sat up, confused.

“They found the lesion,” your father insisted. “They’re closing him up now.”

I leaped out of bed, every part of me quivering like jelly. We banged frantically on the elevator buttons until they opened, then paced outside the recovery room. When you didn’t come out, we sat on a bench. My body swayed from weeks of fatigue and I stunk from perspiration, unwashed and still in my nightgown, having long ago ceased to care how I looked.

When the doors swung open, only the doctors emerged, their faces lit with joy. They were happy scientists who had witnessed what was until then mere aspiration. “Zack’s doin’ great,” said your doctor in his Irish brogue, explaining how the thing that never, ever happened, happened. The surgeon had seen a miniscule “blush” on your pancreas and snipped it out; pathology confirmed it as the lesion. You didn’t even need a transfusion: You lost a mere quarter of a teaspoon of blood.

The surgery was done.

For weeks I had been in a kind of suspended animation, holding my breath, waiting for the nightmare’s end. Now I had another kind of disbelief.

“I don’t get it,” I said to your father. “Explain it again so I get it.”

“They found the lesion on the first try” was all he said, but not unkindly.

I washed and dressed, and two hours later we were again sitting outside the swinging doors. They opened to a posse of nurses and doctors wheeling an adult-sized gurney with a tiny chrysalis in the middle—you. I ran past the no-admittance sign before they were all the way out, and they stopped, but only for a minute. That’s when the picture of you was so indelibly laid down that conjuring the memory even now softens my insides with the somatic imprint of a new mother’s anguish.

They had chilled you for the surgery to minimize bleeding and infection and laid you in a nest of heat-packs. You were pale and swollen with a tube in your nose and another in your mouth. You had red patches around your eyes where your eyelids had been taped shut, and your sprawling limbs were ice-cold. You trailed a bramble of intravenous lines, electrical wires, and drain-tubes that prevented a longed-for hug. But I leaned over and kissed you, and that’s when I registered your eyes.

They were open, your blue-brown pupils big and dark, and cloudy with ointment. Still, through all that swirling haze, you found your mama’s eyes and stared.

I’ve undergone brain surgery; I remember how strange the world appeared from the horizontal position on a gurney, the flashing overhead lights and undersides of faces, and the stiff bloodless feeling that makes not only calling out but crying impossible. You went through a worse ordeal as a defenseless and wordless newborn, and now, you were on the other side. The memory of that moment—your second birth, I call it—reminds me that I will never be a normal mother, and I will never be a normal mother to a normal newborn. I don’t have a funny-charming birth story that I can share with my “chums.” No, I will forever be mother to the dark-eyed babies of the world whose faces I see in footage about poverty, war, and disaster. The big eyes searching for a mother and a father, stirring my insides with the somatic imprint of anguished childhood.

But my memory is not solely about pain. Even when your health still lay in the balance, those big dark eyes were like pools of deep water pierced by sunlight. I glimpsed something like the soul shining up from their depths, the antithesis of shadow, your insistence not only on life, but on life with love.

Four days later, you were home, a bandage covering the incision that horizontally halved your belly. First the scar was red, then it was white. I thought it would fade, but instead it grew as you did, morphing into the faintest crease, curved upward like an extra laugh-line. I have a twin scar in my abdomen from the C-section, although it is not truly a twin because it is lower and smaller, almost invisible. But it is a twin memorial.

Some children with your disorder develop health or learning problems as they get older; some, like or unlike you, live through divorce and even the death of loved ones. But for you, from the first, life was itself the battle. I was right there, fighting alongside you, as was your father. He—unfortunately—was also battling me, and though I don’t understand what drove him, I choose to believe that, at some level, he was as profoundly terrified as I, that we would lose you.

We didn’t. You are a tall and strong young man whom I cautiously expected to grow up to be a handsome shrimp, the doctors having told us surgery might inhibit your growth. That’s another way you have defied expectations. In a phrase I used to detest, you have “landed on your feet.” But more than two decades later, you are still that infant whose clouded eyes gaze out at a big, strange world, and I am that new mother, still calling.

Does anyone know where my baby is?

I hope someday those eyes may meet and return my gaze.

Love,

Mama

Melanie S. Smith is a 2019 graduate of the GrubStreet Memoir Incubator; her work has appeared in Ruminate, The Common, and Cagibi, among others, as well as the yearly anthology of notable writing by women, Ms. Aligned. She has recently finished SCAPEGIRLS, novel about the legacy of intergenerational family trauma, and a collection of essays entitled DRAW KNIFE. She teaches writing and counter story at Boston University.